Food intolerance blood tests measure a person’s levels of IgG antibodies to a wide variety of foods, but IgG antibodies do not have any proven link to illness. At best, these blood tests are a waste of money; at worst, they can lead to poor or even dangerous health decisions.

Despite their inherent ineffectiveness, IgG food intolerance tests have spread to the pharmacy and the doctor’s office, making it hard for the average patient to know where to turn for reliable information. To protect the public, professional medical associations in many countries asked the best minds in immunology to prepare position statements warning against these tests. Let’s take a look at some of the main points from these warnings in plain English.

From the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy [1]:

“IgG antibodies to food are commonly detectable in healthy adult patients and children, independent of the presence or absence of food-related symptoms. There is no credible evidence that measuring IgG antibodies is useful for diagnosing food allergy or intolerance, nor that IgG antibodies cause symptoms. In fact, IgG antibodies reflect exposure to allergen but not the presence of disease.” (full text)

What it means

The most important thing to remember is that everyone produces IgG antibodies to food. The concentration of IgG antibodies in your blood depends on your genes, your diet, and maybe even on how you were fed as an infant [2]. There is simply no ‘correct’ IgG level. This means that a healthy person could get the same diet recommendations from an IgG blood test as a person with symptoms.

Looking at the entire body of available evidence, there is no correlation, let alone a causal link, between IgG antibodies and symptoms. In fact, using IgG test results to identify problem foods is no more successful than flipping a coin.

From the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [2]:

“Food-specific IgG4 does not indicate (imminent) food allergy or intolerance, but rather a physiological response of the immune system after exposition to food components. Therefore, testing of IgG4 to foods is considered as irrelevant for the laboratory work-up of food allergy or intolerance and should not be performed in case of food-related complaints.” (full text)

What it means

You might think that not being allergic to a food – in other words, being “tolerant” to that food – means that your immune system ignores it. Sometimes that happens, but tolerance is often an active process. Regulatory T cells keep the immune system from reacting to potential food allergens, and it is these cells that call in the IgG antibodies by secreting an anti-inflammatory messenger chemical known as IL-10. IgG antibodies are not the sign or cause of anything bad, but rather a sign that a person has eaten and has tolerated a certain food. IgG antibodies have nothing to do with food intolerance.

From the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [3]:

“The test is also being marketed to concerned parents, and may lead to exclusion diets which carry risks of poor growth and malnutrition for their children: for example, the elimination of dairy products, wheat, eggs, and/or other foods found in healthy balanced diets.” (full text)

What it means

IgG blood tests often identify between 5 and 20 suspect foods, so the risk of nutritional deficiencies in children is real if too many foods are eliminated without proper medical support. The bigger issue is whether these tests are actually related to the conditions they are purported to treat, namely ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD); let’s take a look at that.

ADHD. Some artificial colors have been shown to affect behavior in children with ADHD, but this reaction does not involve the immune system, so IgG blood tests are irrelevant for identifying which children might be affected. Other foods have also been shown to aggravate ADHD, but IgG levels could not accurately predict which foods. [4]

Autism spectrum disorder. Since IgG blood tests do not really detect adverse reactions to foods, it is unlikely that these tests would apply specifically to autism. While there is speculation that a ‘leaky gut’ increases the likelihood that IgG antibodies to wheat and milk proteins will be found in the blood of children with ASD, a much-touted paper on the topic actually showed that IgG levels did not correlate with intestinal permeability [5].

This doesn’t mean, though, that someone with autism couldn’t also suffer from food intolerance independent of IgG test results. For parents thinking about dietary interventions for autism, it might be helpful to consider the opinion of registered dietitian Zoe Connor, chair of the Dietitians in Autism group within the British Dietetic Association [6]:

“…[A]lthough there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of any diet as a treatment for ASD, dietitians and other health professionals should provide support when an individual or their parents choose to try dietary changes. There are too many reports of children with ASD improving in behaviour and/or bowel habits after eliminating some foods for them to be discounted. However, the mechanism for this (until proven otherwise) is likely to be the same as for any general food intolerance, rather than any specific disorder that is particular to ASD, and so each case should be considered individually. For example, bowel problems such as diarrhoea or constipation can sometimes be caused by food intolerances, so individuals suffering from these might benefit from trying different food exclusions (medical causes should first be investigated by a doctor).” (p. 66)

From the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology [7]:

“Additionally, and perhaps of greater potential concern, a person with a true immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergy, who is at significant risk for life-threatening anaphylaxis, may very well not have elevated levels of specific IgG to their particular allergen, and may be inappropriately advised to reintroduce this potentially deadly item into their diet.” (full text)

What it means

In true food allergies, IgE antibodies bind with allergen proteins to cause chemicals, like histamine, to be released in the body and trigger symptoms. IgG antibodies are not interchangable with IgE antibodies, and IgG blood tests do not detect food allergies.

We most often think of food allergies as beginning in childhood, but adults can also develop allergies at any time. Perhaps an old allergy returns, perhaps a mild allergy was there in the background all along, or perhaps the allergy is completely new. New allergies to pollen can also bring on food-related symptoms in the form of oral allergy syndrome. Adult food allergies must be taken seriously, because the risk for severe reactions becomes greater the later they develop [8].

Approaching food sensitivities the right way

The EAACI position statement [1] mentions another vulnerable market for food intolerance blood tests – people who see their doctor for a suspected food sensitivity that turns out not to be an allergy but cannot be explained. The doctor dismisses their symptoms, but not their suspicions of food. Feeling let down, they go outside the medical community for care or advice – which is understandable, but never the wise thing to do.

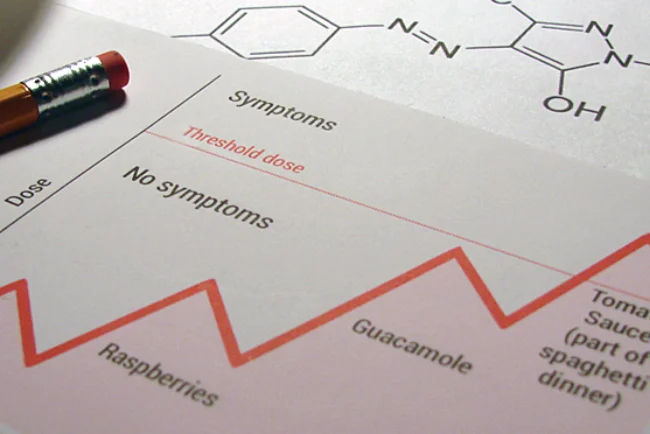

In a case like this, the safest thing is to get a doctor’s referral to see a registered dietitian and discuss doing a diet investigation. Alternative medicine may use rhetoric about ‘hidden food intolerances,’ but a knowledgable dietitian can use your personal history and diet log to guide you through the elimination diet and food challenges that check for food intolerance. In actuality, there is nothing ‘hidden’ about food intolerance, and there is no need to resort to blood tests to find your food sensitivities.

Last updated September 25, 2015

© 2014 FoodConnections. All rights reserved.

FoodConnections.org – The science-based food intolerance resource since 2013

References

1. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. Unorthodox Techniques for the Diagnosis and Treatment of allergy, Asthma and Immune Disorders – ASCIA Position Statement [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2014 Mar 10]. Available from: http://www.allergy.org.au/health-professionals/papers/unorthodox-techniques-for-diagnosis-and-treatment (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6OjZpQGNt).

2. Stapel SO, Asero R, Ballmer-Weber BK, Knol EF, Strobel S, Vieths S, et al. Testing for IgG4 against foods is not recommended as a diagnostic tool: EAACI Task Force Report. Allergy. 2008;63(7):793–6. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01705.x/abstract (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6OjZbB9va).

3. Carr S, Chan E, Lavine E, Moote W. CSACI Position statement on the testing of food-specific IgG. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012 Jul 26;8(1):12. Available from: http://www.aacijournal.com/content/8/1/12 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6OjZmUPVA).

4. Pelsser LM, Frankena K, Toorman J, Savelkoul HF, Dubois AE, Pereira RR, et al. Effects of a restricted elimination diet on the behaviour of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (INCA study): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2011;377(9764):494–503.

5. De Magistris L, Picardi A, Siniscalco D, Riccio MP, Sapone A, Cariello R, et al. Antibodies against Food Antigens in Patients with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:1–11.

6. Connor Z, Autism and autistic spectrum disorders. In: Skypala I, Venter C, editors. Food Hypersensitivity: Diagnosing and Managing Food Allergies and Intolerance. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. p. 63-68.

7. Bock SA. AAAAI support of the EAACI Position Paper on IgG4. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010 Jun;125(6):1410. Available from: http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(10)00512-9/fulltext (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6OjZkm9m9).

8. Kamdar TA, Peterson S, Lau CH, Saltoun CA, Gupta RS, Bryce PJ. Prevalence and characteristics of adult-onset food allergy. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2015 Jan;3(1):114–115.e1.